Lynx paintings - The Iberian Lynx .

Art prints. Lynxes paintings printed on canvas

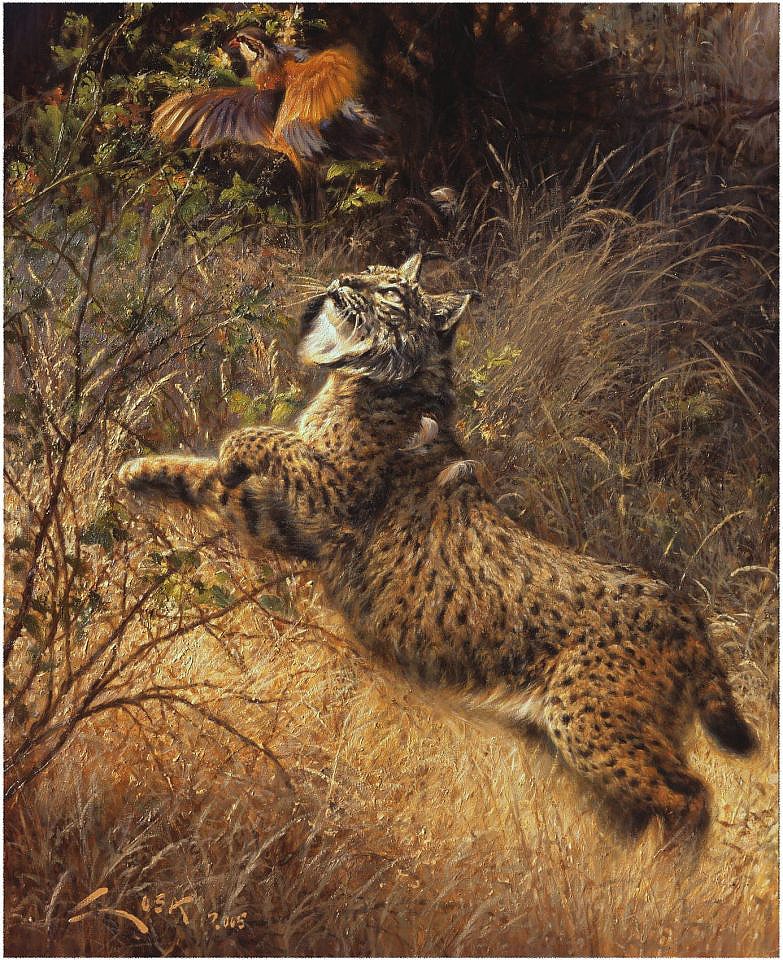

"For the feathers"

Lynx and Red-legged Partridge ( Lynx pardina ) & ( Alectoris rufa )

Pictures of lynxes

BUY A CANVAS PRINT:

You can choose a personal size

varying the original width (cms)

The Mysterious Griffon Wolf

Humpteen, many, many years ago, when stories had only been told in the imagination of men, a handful of Greek heroes led by Jason and aboard the ship Argos set sail in search of the Golden Fleece, guarded in distant lands by an immense dragon. These Greeks, known since then as Argonauts, took as their pilot an exceptional man, able to see through the walls and recognise the bottom of the sea at a glance. His name was Linceanus, and tales of his marvellous eyesight were to circulate for centuries throughout the lands of the world.

known. But the memory of men is weak. Someone, once upon a time, forgot the story of the Argonauts and attributed the extraordinary visual capacity of Lyncean to a mysterious, feared animal, only occasionally seen in the depths of the forest, which was known by a name very similar to that of the mythological hero. Since then, it is proverbial to say of those who see very well that they have a "lynx's sight" and that "they are a

lynx " who quickly realises everything. This story illustrates perfectly what for hundreds of years has been man's knowledge about the lynx, which old chronicles call the fawn, the wolf cat, the wolf wolf and the fawn wolf. A mixture of errors, legends, fear and ignorance. In the Middle Ages," says Lavauden, a famous zoologist from the beginning of the century, "the fawn wolf was the object of superstitious terror.

It was supposed to be very rare, for those who happened to kill a lynx could not accept that this rather small animal was the same beast that was the subject of such terrifying legends. "It was taken for granted that the wolf-cat must be at least as big as the real wolves, with large pointed ears, powerful jaws, huge heavy claws, a striped or spotted back, a long tail ending in a tuft and, above all, a gleaming, diabolical gaze. From that period come paintings of lynxes and many of the figures depicting the devil with something of a big cat, be it the eyes, the claws, the tail or the pointed ears. But the lynx is gradually ceasing to be a mystery. There is still much to be known about its biology, certainly, but more and more scholars are determined to unveil each and every one of its secrets. But knowledge, the end of the mystery, has brought one piece of evidence: the lynx is very scarce, disappearing rapidly from our last forests and will probably be only a memory before we know it well. A vigorous man, with courage and cold-bloodedness, could in fact, without weapons, emerge triumphant from the attack of an old wolf. In a fight with a lynx, he would surely succumb". Such a commendable statement from the mouth of an expert, though no doubt controversial and open to discussion, gives a perfect idea of our cat's powers. Its hands, which are finished with long, razor-sharp, retractable claws, are endowed with terrible strength and move with dizzying speed. Lynxes, at least in Doñana, are stilt-walkers, looking like greyhounds or slender hounds. Their long legs - when you see a lynx in the wild you are surprised by this detail, which is not well reflected in most drawings, pictures of lynxes and photographs - allow them to run fast and jump with enormous agility. In Poland, the lynx has been measured jumping up to 5 m, and even higher if the animal started from the top of a branch. In pursuit of prey, the average length of each stride is about 2 m. In this painting by Manuel Sosa, we can see a magnificent Iberian Lynx hunting a Red-legged Partridge in an oil painting. Its climbing ability is well known, but it is often ignored that its aversion to water does not prevent it from being at least an average swimmer. It is not, however, a good long-distance runner. When the prey is alerted or the first attempt to capture it has failed, the lynx will give up the chase. If it is itself being pursued, it will climb a tree, but if the ground is discovered, it will let itself be caught, exhausted, after a few hundred metres of fast running. And we have already said where the idea of the lynx's extraordinary eyesight comes from. Professor Lindemann used two young captive lynxes that he himself had reared from a very young age to carry out experiments that would inform him about their visual acuity. For this purpose, he placed the lynx at a fixed location and moved stuffed animals in front of it at varying distances. In winter, in the snow, his specimens could see a roe deer at a distance of half a kilometre, a hare at 300 m and a mouse at 75 m. If the hare was white, it could not see a mouse. If the hare was white, however, it would go unnoticed beyond about 25 m. The results seem to denote an animal with good eyesight, certainly, but nothing exceptional. Its hearing, however, does seem far superior to that of a human. Most scientists who have studied the lynx in Europe and America claim that prey is located preferentially by hearing, rarely by sight and almost never by smell. Lindemann's lynxes, on the other hand, could hear a whistle at considerably more distance than a dog could, and at almost twice the distance of a normally gifted human.

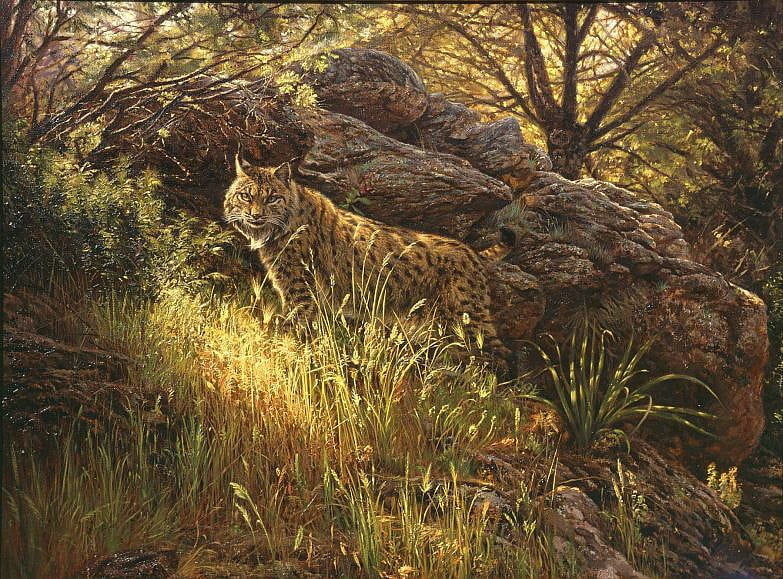

The last Lynx

Property of King of Spain Felipe VI

BUY A CANVAS PRINT:

You can choose a personal size by varying the original width (cms).

The domains of the Iberian Lynx

The European lynx is a forest animal, characteristic of large patches of woodland. It is not uncommon for it to hunt in one type of forest, for example coniferous, but also in another, often deciduous, where hares and deer are more common. It may also happen at certain seasons that lynxes from a whole region move to forests where game is more abundant, as has been observed in Czechoslovakia. Their density then appears to be very high, giving the false impression that they are more common than they really are. The Iberian lynx also seems to require dense vegetation. Its original habitat must have been the Mediterranean forest of holm oaks, gall oaks, cork oaks, wild olive trees, etc., but nowadays it has made its kingdom out of the sea of rockroses and mastic trees, broom and strawberry trees, which characterises the scrubland, where the rabbit was, until myxomatosis, extraordinarily abundant. The requirements of both species of lynxes seem to be dense vegetation cover that provides them with protection and a density of potential prey that guarantees their food. For this reason, one of the greatest threats to their survival is the destruction of native forests and their replacement by exotic woodland, under which, generally speaking, there is neither the necessary protection nor sufficient prey. Is a lynx free in the wild? Perogrullo, on this occasion, would perhaps get the answer wrong. Like many other animals, the lynx cannot move at will through the vast expanses of the forest, but has specific, limited hunting grounds: its territory. If it leaves its territory, it will probably be attacked by other conspecifics and will have to retreat. Little is known about the territoriality of the Spanish lynx. An interesting, as yet unfinished study by a painter in a mountain range in Extremadura suggests that the territories are small (about 300 hectares) and contiguous. In reality, on the basis of what is known about other lynx species, it can be expected that they will indeed be small (given that the rabbit, the basic prey, reaches high densities, and therefore does not require a very large hunting ground) and that they will overlap extensively. Painter observations of a bobcat population in South Carolina indicate that adult females are highly individualistic with respect to other conspecifics of their sex, while the home ranges of males overlap widely with each other and with those of males. The size of the territories of these lynxes ranged from 250 to 500 hectares, i.e. very close to that which the painter estimates for Spanish lynxes. In Sweden, however, the situation is quite different. The territories were also large, but their size exceeded 30,000 hectares in the case of an old male, and was only slightly smaller in the case of a female and her cub. The size of the home range seems to be closely related to the distance travelled daily. Thus, while a lynx in Sweden moves 15 to 20 km per day, a bobcat in Carolina moves about 3 to 4 km (strictly speaking, 2 to 5 km). This suggests that the range of the Iberian lynx, which seems to have a small territory, will not exceed 5 km per day either, and will probably be considerably less. How does a lynx recognise its neighbour's territorial borders, and how does it recognise those of its own territory? Although there are several mechanisms, the main role seems to be played by olfactory signals, mainly based on droppings and urine. Contrary to what has often been said and painted, the lynx only rarely buries its faeces, at least in Spain, and when it does it is always in inland areas of its territory. On the roads and paths that border it, on the edges, the fawn wolf accumulates excrement in very visible droppings, which undoubtedly play the role of boundary markers. As for urine, throughout its march the lynx continually raises its tail and releases small streams of urine to the right and left - both males and females can direct it directly backwards - which will later serve as a fragrant calling card for any conspecific travelling through the same areas. The meaning of this presentation seems obvious: "occupied ground". Hunting day Self-confident, endowed as he is with few enemies other than man, the big cat puts all his faculties at the service of the hunt. It is these faculties, in harmony, that make him the hunter par excellence. Although it is often observed during the day - more the Iberian lynx than the northern lynx - its activity is mainly nocturnal and twilight. When the reddish sky gives way to the first shadows, accompanying the early cry of the owl, the lynx wakes up in its bed of grass and leaves where it lies down the previous morning. It stretches out its paws indolently, yawns, nervously moves its ears topped by long brushes and slowly, without any apparent haste, starts to walk. A very beautiful moment to portray the Iberian Lynx. By this time the magpies are already asleep, but perhaps a delayed jay will disturb him with its cries, which announce the proximity of the hunter to the forest community. They always move at a walking pace, and only when trying to stealthily escape from a threat will they break into a long trot, followed by huge, fast galloping leaps if danger approaches. The hunting technique is simple. As it moves along the path opened up in the thicket by deer, roe deer and wild boar, the lynx looks around and, above all, listens. A slight noise, monotonous and imperceptible to human ears, catches his attention and suddenly immobilises him. His body drops to the ground, his limbs bent, his gaze fixed. A hare eats in a small clearing, no more than 50 m away. Muscles tense, stealthy like a reptile, beautiful and elastic like all felids, the hunter stalks his prey in a cautious approach that can last for long minutes. The hare, oblivious to everything, is now less than 10 m away, and the lynx has stood still, shrinking as if it were a spring.

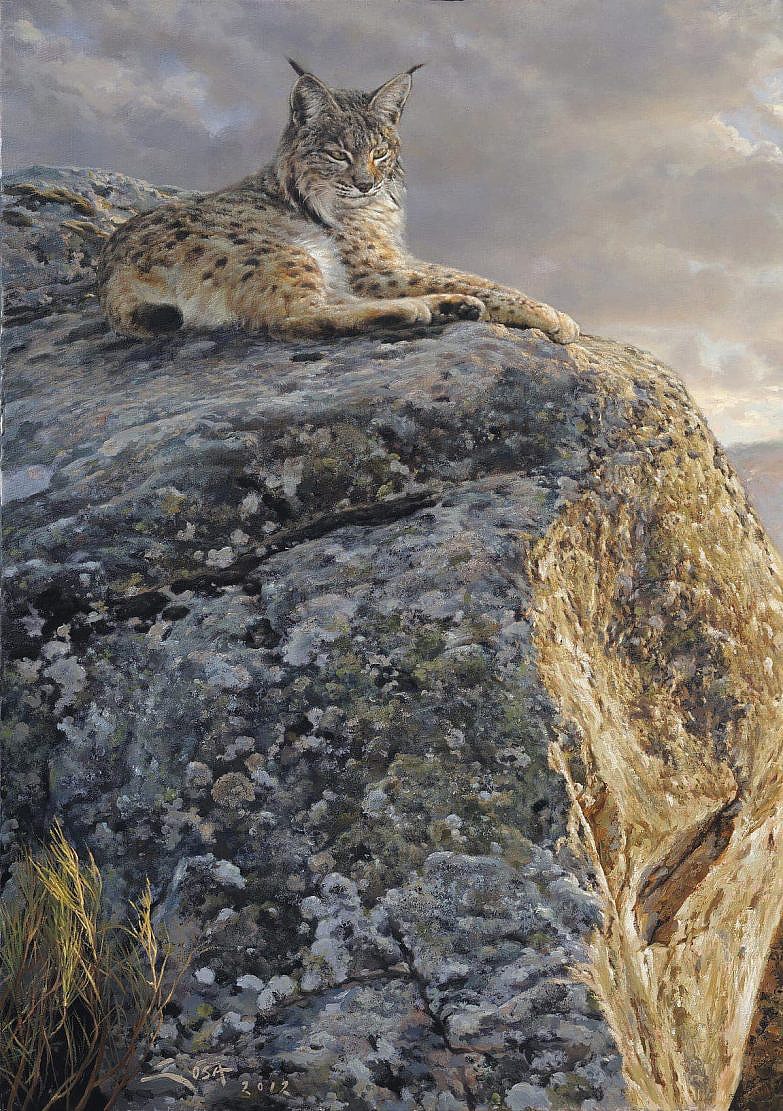

The day falls for this big cat, Iberia's carnivorous jewel. Proud, haughty, and now pampered, with little more than a hundred brothers alive on the planet. Another of my compositions in inverted 'L', only broken by the torso of the feline. A painting of a large Iberian Lynx lounging on a rock enjoying the last remnants of sunshine. A painting by Manuel Sosa © 2012.

The lynx menu

It is undeniable that lynxes specialise in catching lagomorphs, i.e. hares and rabbits, although in some areas, where these species are not common, it is ungulates, mainly, in Europe, roe deer, which pay the heaviest tribute to the king of forest hunters. In Spain, we are now beginning to know with concrete data what the lynx's prey is, and in what proportion, and it is to be hoped that ongoing studies, mainly in the Coto de Doñana, will enable us to establish this more precisely. Miguel Delibes, together with Fernando Palacios, Jesús Garzón and Javier Castroviejo, have been able to analyse 16 digestive tracts of 16 lynx which, unfortunately, had been poached in Sierra Morena and the Montes de Toledo. They also examined 37 droppings collected in the sierras bordering Cáceres and Salamanca, possibly the most northerly enclave of the species, unless it still exists in the Pyrenees. The results of these analyses allowed them to establish that the 85 prey items ingested by the Iberian lynx included 48 rabbits, 3 hares, 13 voles, 3 dormice, 3 voles, 2 common rabbits, 2 unidentified rodents, 3 thrushes, 3 partridges, 4 undetermined birds and 1 lizard. In Doñana, the diet is somewhat different, with rabbits, ducks and ungulates gaining in importance and rodents losing in importance. Out of 126 prey items elucidated from scat analysis, there were 11 rabbits, 5 rodents, 2 young deer or fallow deer, 7 ducks and 2 birds of other genera (one of them probably partridge). In any case, it is clear: a) that the Spanish lynx feed basically on rabbits, so myxomatosis must have dealt them a blow of incalculable consequences; b) that deer and partridges are hardly important in their menu, which is highlighted if we take into account that fallow deer, deer and partridges are extraordinarily abundant in Doñana. Both conclusions force us to consider irrational the persecution to which lynxes, like other carnivores, are subjected in large game reserves, where it is often necessary to resort to professional trappers to limit the number of rabbits. On the other hand, as we shall see, the lynx is the main protagonist in limiting the population of other carnivores, especially the fox. The lynx has traditionally been known as a cat and a fawn wolf because of its ability to capture and kill deer, which are much larger than it is. To carry out performances of this kind requires a perfected killing technique, which our cat does not lack.t is undeniable that lynxes specialise in catching lagomorphs, i.e. hares and rabbits, although in some areas, where these species are not common, it is ungulates, mainly, in Europe, roe deer, which pay the heaviest tribute to the king of forest hunters. In Spain, we are now beginning to know with concrete data what the lynx's prey is, and in what proportion, and it is to be hoped that ongoing studies, mainly in the Coto de Doñana, will enable us to establish this more precisely. Miguel Delibes, together with Fernando Palacios, Jesús Garzón and Javier Castroviejo, have been able to analyse 16 digestive tracts of 16 lynx which, unfortunately, had been poached in Sierra Morena and the Montes de Toledo. They also examined 37 droppings collected in the sierras bordering Cáceres and Salamanca, possibly the most northerly enclave of the species, unless it still exists in the Pyrenees. The results of these analyses allowed them to establish that the 85 prey items ingested by the Iberian lynx included 48 rabbits, 3 hares, 13 voles, 3 dormice, 3 voles, 2 common rabbits, 2 unidentified rodents, 3 thrushes, 3 partridges, 4 undetermined birds and 1 lizard. In Doñana, the diet is somewhat different, with rabbits, ducks and ungulates gaining in importance and rodents losing in importance. Out of 126 prey items elucidated from scat analysis, there were 11 rabbits, 5 rodents, 2 young deer or fallow deer, 7 ducks and 2 birds of other genera (one of them probably partridge). In any case, it is clear: a) that the Spanish lynx feed basically on rabbits, so myxomatosis must have dealt them a blow of incalculable consequences; b) that deer and partridges are hardly important in their menu, which is highlighted if we take into account that fallow deer, deer and partridges are extraordinarily abundant in Doñana. Both conclusions force us to consider irrational the persecution to which lynxes, like other carnivores, are subjected in large game reserves, where it is often necessary to resort to professional trappers to limit the number of rabbits. On the other hand, as we shall see, the lynx is the main protagonist in limiting the population of other carnivores, especially the fox. The lynx has traditionally been known as a cat and a fawn wolf because of its ability to capture and kill deer, which are much larger than it is. To carry out performances of this kind requires a perfected killing technique, which our cat does not lack.

In the picture above, a lynx can be seen magnificently in a cast towards a partridge.

Although it has rarely been depicted in paintings, the lynx generally attacks large animals by leaping at their necks, so that once it has been held in its claws it can use its canines to make a prey in their throats, causing death by suffocation. At the scene of capture, there are usually no signs of a struggle, which has caused some surprise among scientists, given that it must take a long time to asphyxiate a large ungulate, and these are animals of considerable size which, even if they fall to the ground, should be able to defend themselves. Ethologists now think that the shock suffered by the prey when it suddenly sees the lynx on top of it is of such a nature that it causes a paralysis of terror. Observations carried out by Miguel Delibes in Doñana on freshly killed prey show that the bite on the neck is also the usual way of killing smaller animals, such as rabbits and geese. Prey killed in the clearings are usually transported to a hidden place to be eaten there. Valverde has reported the case of a rabbit that fell into a trap and was carried, trap and all, more than a kilometre, and a young deer was dragged 140 m away. These are certainly exceptional distances, and there are known cases where the victim has been eaten practically in the same place where it was killed. This also seems to be the case with the northern lynx, which usually hunts deep in the forest, although pictorially, not as beautiful as the Iberian lynx. The Swedish painter Haglund has written: "The lynx shows very fixed patterns of behaviour, which it is almost incapable of changing. Its habit of hunting in one place, eating there, sleeping there and then starting a new hunting party far away from the previous one, distributes the tribute of prey animals over a wide area. This keeps the density of small game above a minimum limit, which is advantageous for him. As far as big game hunting is concerned, however, the method seems uneconomical". Indeed, if the lynx captures a young deer and after eating it, leaves the area, and therefore the prey, in search of new raids, it will not get to consume it in its entirety. Normally, the lynx in Doñana devour 1 or 2 kilos of meat from the knuckle or thighs, leaving the rest, which is not visited again, half-buried in the sand or simply hidden among the vegetation and which will be eaten by wild boar. Rabbits are generally eaten entirely, excluding the intestinal tract, and birds, which are clumsily plucked, are also eaten. There is not a single known case in which the Spanish lynx has gone to the carrion or eaten again from a prey abandoned in previous days. This, however, does not seem to be uncommon in the rest of Europe and North America, with boreal and Canadian lynxes being the protagonists. In Czechoslovakia, for example, a lynx was killed at night, mistaken for a fox, while eating a horse carcass, while a study in Canada found that lynxes came to dead domestic livestock and dug up half-digested hares, previously hidden, to finish eating.

Lynx in the fog

Lynx lynx (Lynx lynx)

Lynx table

| BUY A CANVAS PRINT: You can choose a personal size |

Alynx will rarely kill more than one prey in a single night, and there will be several that will not be successful on his part and he will have to draw a blank. However, there will be no shortage of attempts, for the bobcat, however well trained and gifted it may be for hunting, does not always succeed. The best shotgun, the best hunter, sometimes misses a shot, and the killing machine that is the lynx is by far no exception. A slight gust of wind, the snap of a twig or the roll of a pebble can alert the prey and spoil everything. Several scientists in North America and Sweden have studied the success and failure rate of the lynx's hunting day, based on the hunting diary, clear to the expert eye, which all animals leave written in the snow after their passage: the tracks. The results obtained, why not say it, tarnish a little the image of the peerless hunter that we have been presented with of the lynx. Or perhaps it is truer and fairer to say that they enhance the image of roe deer and deer, rabbits and hares, partridges and mice that have so often been considered mere scapegoats. In Sweden, lynxes studied by Professor Haglund attempted to capture roe deer on 44 occasions. On 9 of these occasions, the presumed prey discovered the predator and fled without giving it a chance even to attempt capture . On 12 other occasions the attempt was made, but was unsuccessful. The percentage of roe deer shot was therefore slightly higher than 50 % of the sets . Successes were more frequent when hunting reindeer which, perhaps due to domestication, were less able to detect danger. Of 65 reindeer stalked, 64 were attacked and 45, approximately 60 % were killed. Small game, on the other hand, seems much more difficult to catch. Only 35 % of the attacks on hares, 29 % of those on aurochs and 19 % of those on clowns and lizards were successful, while there were quite a few occasions when these animals, alerted, escaped from the predator. Nellis and Keith's studies on Canada lynx give even poorer results. Of 98 hares attacked, only 16 (about 16 % ) were apprehended. With lizards the success rate dropped to 12, and with squirrels to 8 (only one squirrel killed in 13 hunting attempts). In all cases, biologists agreed that the percentage of successful captures was related to snow conditions. Soft snow, which does not support the weight of the lynx without giving way, will hardly allow it to take the necessary impulse for the next jump. Hunting in such conditions has no chance of success and often the spotted cat will not even attempt it, passing by its prey without so much as a glance. The lynx and the fox In Spain, and in much of Europe, the fox has become a veritable plague, as it is free of obstacles to its demographic expansion. In the past, the lynx was undoubtedly one of the obstacles, and where it still exists, it controls and keeps the overabundant canid at bay. Such is the case in Doñana, and no doubt anywhere else where the bobcat is common. The lynx-fox animosity is probably a consequence of competition for very similar trophic resources. Quite often, however, the confrontation becomes direct, and in the battle it is the fox that stands to lose. It is killed in the same way as other prey, by a sustained bite to the throat, but is rarely eaten afterwards, its enemy merely covering it lightly with sand or vegetation. Cases have been reported of lynx penetrating a fox den to kill, and sometimes semi-devour, the young. Moreover, tracks in the snow have proved that the fox, at least in Scandinavia, eludes the proximity of the cat, turning back at full speed, and making long detours, whenever its sight or sense of smell leads it to suppose that the enemy is near. In Spain there are stories of wild cats, foxes, otters, mongooses, genets, etc., killed by lynxes. On one occasion, too, traces of mongoose have been found in faeces of a wildcat. In Sweden, lynxes studied by Haglund attacked foxes, stoats and martens. The same author found traces of fox in two of the stomachs he was able to examine. In North America, on the other hand, some cases of cannibalism have been discovered, probably involving females who in times of scarcity had devoured one of their starving offspring. Super-predatory tendencies are common in medium to large felids. In particular, some leopards studied in Norongoro Crater and the Serengeti killed more jackals at certain times than gazelles or monkeys - their natural prey - and were also seen and photographed killing a fawn and a lion cub. It is quite possible that the irresistible attraction that the rabbit's "squeal" exerts on the lynx is more in the service of the search for and killing of the ecological competitor - cat or fox - that has captured the animal in its fiefdom than in the capture of the rabbit itself. In any case, in rabbit baiting campaigns, many lynxes fall between the iron jaws of the traps, attracted by the agonised cry of a rabbit caught in an immediate trap. The decisive importance of the presence of top predators such as the lynx in our countryside is evident, in order to maintain the right density of more prolific predators such as the fox, whose populations skyrocket as soon as their natural controllers disappear.

Iberian Lynx - Portrait

Iberian lynx ( Lynx pardina )

Pictures of lynxes

| BUY A CANVAS PRINT: You can choose a personal size |

Time for love

The lynx is a sullen and introverted animal. Only the rut will keep the pairs together for a short period, and later the maternal instinct will keep the mother with her cubs for several months. At the end of January and in February, in Spain, when spring can only be glimpsed in the slight shortening of the nights, the fawn wolf's loves are at their peak. In Europe everything will happen a month or a month and a half later. Then, in the twilight and darkness, the hoarse, mournful mewling of the male is heard, which is only occasionally answered by his partner. During the day, they are seen together, sitting in the sun by the side of the roads. Sometimes several males quarrel, and fierce fights may end in the death of one of them. At other times, male and female hunt together. Once a prey is located, one of them marches to a strategic place where the prey is supposed to pass. The other partner, acting as a scout, marches straight towards her, harassing her until she is forced to pass the hidden hunter's position. After the usually fortunate outcome, the couple lovingly share the spoils. Biologist McCord has described, with all the limitations imposed by relying solely on "reading" tracks in the snow, the courtship and mating ceremonies of the American bobcat, the species most similar to our Mediterranean lynx. According to his observations, the bobcat would be polygamous and there would be no open confrontations between several males following the same receptive female. On the other hand, it could be the case that the courtship would establish a kind of hierarchy between them without the need to resort to direct confrontation, but by means of threats, both in the form of vocalisations and postures or facial expressions. Courtship seems to include many elements already found in the play of young carnivores. One member of the pair, the more active and probably the male, runs around his mate, inciting her to chase. At other times, in what McCord calls "ambush" behaviour, he dives under a log, a rock or a bush, leaping at his mate and setting them both off on a mad dash. As the amorous tension builds, the male tries to approach the female, who may respond with some violence, but no blood is ever shed. Later, however, after the heads have interlocked (as Spanish and European lynxes have been seen to do in captivity) or they try to nibble each other's necks for a few metres, copulation takes place, resulting in a small hole of about one metre in diameter in the snow. It can be assumed that during mating the male bites his partner on the back of the neck, as other felids often do, as in all cases the American researcher found small tufts of hair, most probably from the nape of the neck, next to the ceremonial tracks. The period of receptivity of the females seems to last for more than a week, during which they may be covered by several grooms. Gestation is then somewhat longer in the northern and Canadian lynx than in the smaller, southern bobcats and Mediterranean lynx (approximately 10 weeks in the former and just over 8 or 9 weeks in the latter). The cubs Separated from the male, the pregnant female cat walks around, as if unaware of her condition, for more than a month and a half. Only then does she seem to settle definitively in a small area, where she chooses the site for the nest. Valverde, in Doñana, has reported nesting in hollows of cork oaks (four times), among the densest vegetation of heather, junipers, mastic trees, etc. (five times), in old stork nests on pine trees (twice). The future mother usually piles up grasses and branches to form a comfortable bed, which is then used during the birth and the first weeks of life of the young. She would never, according to Dr. Valverde, use her own hair for this purpose. Most births in Spain take place in March and April. Small kittens have, however, been seen in January and June, suggesting some variability in the time of oestrus. It is known that the bobcat may eventually have two litters per year, but there is no indication that this is the case for the Spanish lynx. Both the European and Canadian lynx breed only once a year and at a more fixed and constant period than the other two species. Each female Mediterranean lynx gives birth to 1 to 4 cubs, which are born with their eyes closed. The most common number is 2, but births of 3 are not rare, while 1, 4 and especially 5 seem exceptional. The small ones, which open their eyes between 8 and 10 days of life, do not weigh more than 250 or 300 g at birth, although there seems to be considerable individual variability in this respect. The assertion that the male collaborates with the female in the rearing of kittens seems to be unfounded, at least as a general rule. Rather, it should be considered that the female behaves like a model mother, who not only defends, cares for and feeds her offspring, but also provides for her own sustenance without any outside help. When the cubs grow up a little and are able to leave the den, they accompany their mother on her forays. They are then charming little cuddly balls, with mischievous, transparent faces and huge green eyes. Their appearance and mannerisms are a far cry from the fierceness that adults can show. They play incessantly. They run, chase each other, climb on top of each other with retracted nails, bite each other, purr, constantly tease their mother, exercise all their muscles in playful and harmless fights and chases. With enough prey and a mother capable of getting it, life is no problem for them, or so they seem to imply. For such vulnerable animals as carnivore cubs, before they are fully trained in hunting and finally emancipated, dependence on the mother is essential for survival. When carnivores are not social - unlike lions or wolves, among which adoption and nursery are common - when they live in a tangled environment where it is easy to get lost and, as if that were not enough, their sense of smell is mediocre, the mechanisms for maintaining family contact must be exquisite. In the case of lynxes - poor of sense of smell, inhabitants of one of the darkest environments, absolutely homochromatic and terribly individualistic - mothers and offspring locate each other and maintain contact by sight and hearing. And the short, striking and characteristic tail of the lynx, ending in a black tassel, framed at its base by a light stripe, is of extraordinary importance in the optical control. When lynxes advance through heather, rockroses or strawberry trees, their short, upright, vertical tails move nervously, like a small traffic light that glistens with every ray of sunlight. The size of the lynx allows the small heliograph to stand out many times over the grassland or undergrowth, always on the move, as if trying to attract attention.

A skilful Iberian Lynx catches an elusive hare by surprise. This painting is an oil painting on canvas. Manuel Sosa © 2021

On the verge of extinction

The history of lynx distribution in Spain and Europe points in a very clear and definite direction: ,extinction. Only recently, with their reintroduction in some countries and serious protection in others, do more promising prospects seem to be opening up for the future of Europe's last big cats. According to studies by the Czech biologist Kratochvil, at the beginning of the historical era, lynxes lived almost everywhere in Europe, except for Great Britain, the Netherlands, Denmark and part of Greece and Portugal (?). Their rarification was slow and gradual until the 19th century, when they still existed in the least populated and most forested regions of almost every country on the continent. Since then the rate of disappearance has increased dramatically. Already in the 20th century fawns have ceased to be part of the fauna in Italy, Switzerland, Hungary and France (it seems unlikely that lynxes, European or Mediterranean, exist in the French Pyrenees), having done so earlier in other countries such as Austria and Germany. Today, European lynx populations can be considered reduced to four: the Iberian Peninsula, the Balkans, the Carpathians and Scandinavia, Russia and Poland. Apart from the Iberian lynx, Lynx pardina, and the more northern populations, included in the Lynx lynx species, some authors consider the populations of the other two large areas as subspecies of the boreal species: Lynx lynx balcanicus, Lynx lynx carpathicus and Lynx lynx lynx lynx, but most do not admit it. In any case, much remains to be clarified about the taxonomy of the European lynx. Very recently, the fawn wolf has been reintroduced in Bavaria (Germany). The marked reduction of the Iberian lynx's range seems to be quite recent. In the Bronze Age, according to archaeological finds, it was present almost everywhere in the country. It still existed in Vasconia in the 18th century, and in Galicia in the mid-19th century. In this respect, the notes of the Spanish naturalist Mariano de la Paz Graells in his book Fauna M astodológica Ibérica , which, although published at the end of the last century, was written in the middle of that century, are of great interest. In it we read: "I have found it in the mountains of Guada rrama, and it has even entered the garden of the small house below the Royal Heritage in El Escorial... I have received specimens to exchange with other museums in Europe hunted in Andalusia, Extremadura, Cuenca, Sierra Morena, Salamanca, in Las Batuecas and in Palencia and Asturias.

SHARE IT ON

The authors

Article from the encyclopaedia of the Iberian fauna by Felix Rodriguez de la Fuente, illustrated with the paintings of the Iberian Lynx by the painter Manuel Sosa. You are invited to enjoy his complete work on the website of his gallery. https://manuelsosa.com