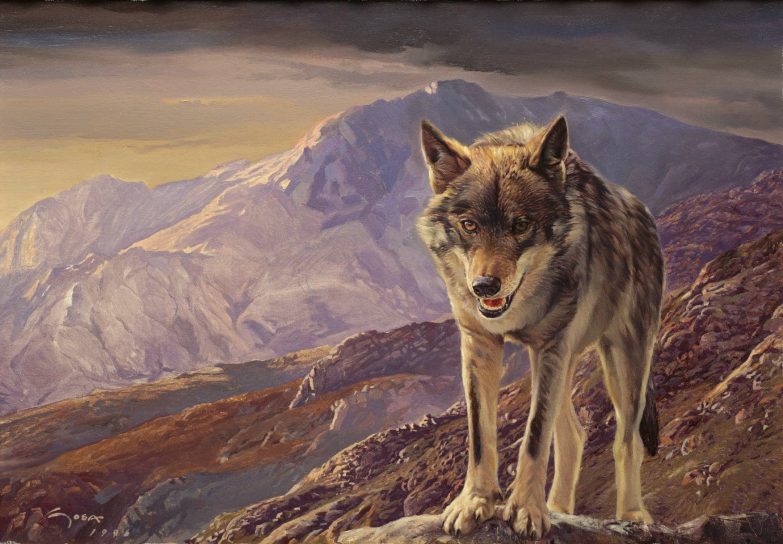

The Iberian Wolf

Portrait of the wolf 'Kirke'. The sunset looms over the deforested peaks, foreshadowing the definitive disappearance of the species. The wolf, in the foreground and tired of fleeing, seems to be begging for mercy but without losing its natural pride. Today there is still a price on its head. Oil on canvas. Manuel Sosa © 1996

The Last Wolf

Iberian wolf ( Canis lupus signatus )

Wolf paintings

BUY A CANVAS PRINT:

You can choose a personal size

varying the original width (cms)

The mythical figure of the wolf

.From ancient times, paintings, pictures of wolves, mythology and folklore have depicted the wolf (Canis lupus) as a diabolical entity to be conjured. Let us remember the "luperealias'', deeds of the Greeks and Romans in which the wolf was the central motif of rites intended to promote the fertility of livestock and at the same time to neutralise the evil predatory power of the wolf. In the Basque Country the " Otsabilko '' or days dedicated to the wolf were celebrated. In Slovenia, Russia and Bulgaria, forest spirits could assume the form of a wolf and used to appear to wanderers in order to lead them astray in the forest. The wolf has been depicted in paintings since the beginning of mankind. Lycanthropy, a mental illness that seemed to afflict human beings and, according to tradition, turned those affected into real wolves that impregnated animals and people. The legend of the male who, as the seventh son of a family of boys, was fatally destined to undergo the process of transformation into a wolf, survived in 18th century Spain to the point that the Inquisition prosecuted supposed lycanthropes. According to the historian Apianus, the Celtiberian tribes of north-eastern Iberia had adopted the figure of a wolf as their symbol. It appears on the coins of Lerda (Lerida), and the heralds covered their shoulders with a wolf skin. Pictures of wolves: there are innumerable references to the wolf in painting, literature and popular songs, and the animal is certainly never portrayed in a good light. For according to these references, the wolf is a bitter enemy of man; its treacherous and petty nature must make it the object of general resentment; its very appearance is ominous, and its danger knows no bounds. This has been, more or less, the image which past generations have handed down to us. But the scientist and the artist must set the record straight. When we observe an adult wolf, we are struck by its robust head, with its pair of triangular ears, and its oblique amber eyes. Its robust neck gives a hieratic impression, so much so that at first glance it seems that the animal cannot turn its head. The skull is narrower than that of the dog, but it is covered with a formidable muscular mass in the temporal region which gives it its characteristic bulkiness; the muzzle is pointed, and the muzzle is more pronounced than that of the dog; the strong canines, the butcher's teeth, betray the tremendous possibilities of the jawbone in the service of predation. In the wolf, the upper butcher's molars usually exceed the length of the butcher's tubercles, which is not the case in the dog. The depressed lumbar region of the wolf's back is accentuated by the long, hairy tail, which is kept slack when walking and hunting, as this prevents it from alerting its prey. The tail shelters the animal's muzzle when it is lying down and is a unique tool of intraspecific communication in group hierarchy clashes. They weigh between 27 and 68 kg, but some specimens have exceptionally exceeded 90 kg. The weight of the Iberian wolf ranges from a minimum to a maximum of 55 kg. This is a function of its smaller size and more wiry appearance than its boreal counterparts. In order to withstand the rigours of the harshest winters, the wolf has a winter coat, which shelters the animal on a layer of greasy down. This type of seasonal adaptation, common to many other species, considerably modifies the canine's appearance and is more pronounced in regions where low temperatures are more extreme. In contrast, wolves that have evolved in regions with milder climates have not had to resort to the addition of such an exuberant hairy coat. Generally speaking, Siberian and Nordic wolves in Europe have a thicker and lighter coat than their Central European or Mediterranean counterparts. Among these, and within the Iberian Peninsula, the wolves of the Cantabrian and northeastern border are darker than those of the Sierra Morena. When the thick fur that the wolf has worn from November to April is shed, it reveals a gaunt and sometimes even emaciated body, which betrays the hardships suffered during the harsh winter. The greyish, dark winter colour gives way to a brownish or brownish tinge on the legs, more saffron on the belly and lower end of the tail than on the rest of the body. Nowadays, melanism in European wolves is exceptionally rare. However, this phenomenon did occur with some frequency in some countries centuries ago. In Switzerland, in particular, there were black wolves in the eastern part of the country in the 16th century, in Germany some black wolves were found in Saxony. A wolf can live up to thirteen or fourteen years, although in the wild it is unlikely that most individuals will reach this age. The increasingly difficult conditions in the ecological environment due to human intervention certainly do not allow for a normal development of the species. A greyish tinge to the fur is indicative of an old wolf. These animals generally roam their usual fiefdoms alone and do not usually compete with younger individuals during the breeding season. Painters and scientists have differentiated the different wolf populations throughout the northern hemisphere into 23 subspecies. Only one subspecies, Canis lupus signatus, is found on the Iberian Peninsula. At the beginning of the century, the great naturalist Cabrera identified a supposedly different breed from the present one, smaller in size and more reddish in colour, located in a corner of southeastern Spain, but of which no trace exists today.

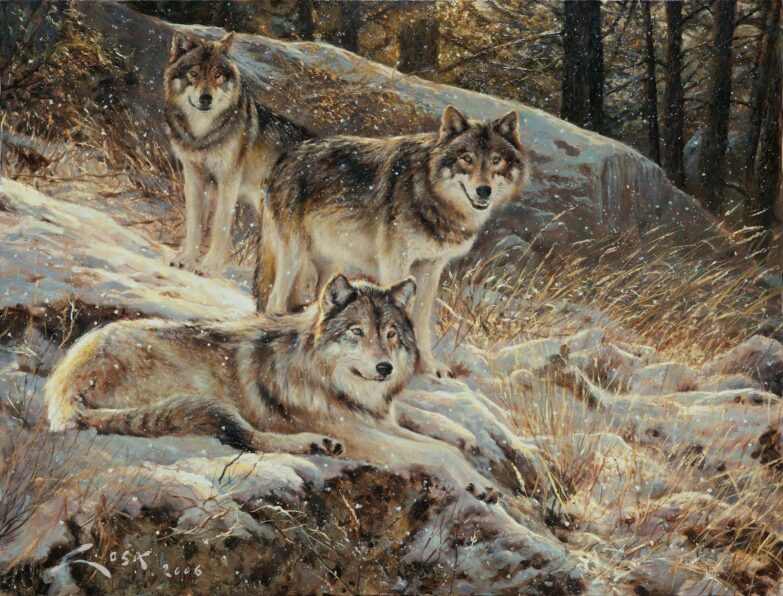

The Pack. Iberian wolf

Wolf ( Canis lupus )

BUY A CANVAS PRINT:

You can choose a personal size

varying the original width (cms)

Before man monopolised the different energy sources in his natural environment, ungulates in their wild state were persecuted indiscriminately by all predators, including man. The wolf found its food, therefore, in the immense protein reserves that would constitute the herds of herbivores that roamed the open AND frozen spaces of the ice age: deer, moose, reindeer, fallow deer, caribou... With the Neolithic revolution and the subsequent process of domestication, competition for food sources between man and other predators increased, and man sought to reduce this competition by using all kinds of traps and ingenuity in the endeavour. The wolf, on the other hand, while occasionally killing herbivores not yet decimated by man, parasitised on man whenever possible, as it has done to this day. Indeed, the dramatic wolf-sheep relationship has typified like no other the oldest stories and paintings of wolves, since pre-Roman times, until it is imprinted in the works of famous painters and writers from Plautus and Terence to the most popular fabulists such as Aesop or storytellers such as Pe rrault. But the wolf is obviously not in the nature of a wild boar when hunger gets the better of him, although the price to pay for it is often too high. For example, there is a case reported by a gamekeeper in the Ancares region of León, in which a wild boar was attacked in the snow by three adult wolves. After a fierce fight in the course of which the snow was beaten and full of blood in a radius of 25 m, the attackers managed to kill their victim, but not without the latter having first maliciously mauled some of them. We will finish by referring to the danger that the poisoning of animals considered harmful to the wolf, and of which it eventually consumes some of them, represents for the wolf. In fact, the death of a wolf from the ingestion of carrion of foxes and other animals affected by the uncontrolled use of poison has been recorded on several occasions. The fact that the wolf is a consumer of carrion partly explains the fantastic stories of people being devoured by the terrible animals. It is true that the wolf may indeed eat the carcass of a man who has died in the field, but this in no way presupposes an attack and death of that person by the carnivores. Natural herbivore selection The normal selective exercise carried out by wolf populations on traditional game species has been interfered with by man since ancient times. Driven by an atavistic instinct, man has killed, at all times and in all places and in a totally indiscriminate and abusive manner, all kinds of animal species. Such uncontrolled actions - which have not yet been stopped - have destroyed the perfectly structured and continuous functioning of the existing food chains of animal communities. The suppression of wild ungulates, the deforestation of wooded areas, the alteration of the most diverse habitats through exploitation of all kinds, road construction, environmental degradation, humanisation of the landscape, etc., predators - like other animals - have had to adapt to the unnatural conditions imposed on their living environment by man. The important role played by any species in the fulfilment of a specific mission is well known, and the wolf is no exception. The wolf's participation in the control of herbivores is not only direct, but the canids also force them to move periodically, thus avoiding the degrading effects of excessive browsing that would seriously damage the vegetation cover. On their own, lithophagous animals would find it difficult to maintain the balance between themselves and the plant matter to be consumed. On the other hand, a lack of large predators - wolf, lynx - would lead to a demographic explosion in the ungulate populations with the subsequent pressure on vegetation, which would upset the balance between population and natural resources and ultimately lead to a gradual degeneration of the vegetation. The elimination of weaker or tardy ungulates is also the responsibility of the canid. In this respect, it can be said that out of nine observations made in the northwest of the Iberian Peninsula in which the wolf reached and killed so many deer, three of them were males with deficient antlers, a fourth one was visibly browsing, and another one had been bitten by dogs and was bleeding when two wolves hunted it. Certainly, the action of man, in his attempts to supplant the natural work of predators such as the wolf, leaves much to be desired, to the extent that the exercise of hunting, even in the best of cases, only serves to exercise a dubious artificial selection, guided by very particular interests and considerations. The reason for the above is very simple and is based on an ecological axiom that we could express by saying that in the vital relations existing between all the communities on the planet, instinct, as a mechanism of conservation AND perfection of these communities, polished countless times by action, repeated a thousand times over the centuries, is above any substitute that man tries to put forward for a similar purpose by means of any intellectual process.

Love and war. Pictures of wolves

Many zoologists consider the wolf to be the direct ancestor of the dog. And among the many wolf breeds, some researchers have chosen the Indian wolf (Canas lupus pallipes) as the most likely ancestor, among other reasons because it barks and does not howl. Others, taking more into account the diversity of dog breeds, suppose that other wolf breeds may also have been involved in the early stages of dog differentiation. Be that as it may, the fact remains that the dog appears as a regular companion of Magdalenian and Protolithic hunters more than 10,000 years ago. Since then, this nesting dog has undoubtedly rendered great services to mankind. But it is not all praise for the dog. In many places they return to a semi-wild state, becoming so-called feral dogs or maroons. These dogs often associate in packs, preying ferociously on domestic livestock and alarming public opinion, which, under the cover of sensationalist news propagated without foundation, blames the wolf for everything. The investigations carried out by J. Garzón, R. Grande and other naturalists allow us to suppose that the figure of losses in livestock due to marauding dogs reached almost two million pesetas in 1975; to these losses should be added the damages caused to small game. The figure re-captured in 1975 in the province of Cáceres for a pack of bighorn sheep, which killed 200 lambs and sheep, is eloquent. Apart from the danger to livestock posed by the existence of bighorn dogs, humans are also exposed to attacks by these canids, although fortunately this does not happen very often. However, according to R. Grande, there is a singular boldness in these dogs, which in many cases are not driven away by the presence of humans. In the wild, hybrids can also sometimes occur as a result of mating between a dog and a she-wolf - more rarely between a wolf and a bitch. This happens especially where wolf densities are very low. Sometimes the identification of hybrids is very difficult, as there is a phenomenon of genetic reabsorption whereby hybrids tend to acquire the purest primitive traits. However, there is never a total identification with the pure forms, for example, the presence of extra nails on the hind legs is an exclusive feature of the domestic dog, which never appears in the wolf. The prosperity of maroons and hybrids is directly related to the destruction of the environment, which has been more intense than ever in recent years, as well as to the irresponsible abandonment of domestic dogs, often in the bush. The spread of the marauding dogs is slowed down by wolves in those areas where they are still abundant. It is well known that wolves and lynxes control the populations of other smaller predators, which may act as ecological competitors. Under normal circumstances, a wolf will not tolerate the presence of dogs in its vicinity, and even less so if they encounter it in its hunting territory or during the breeding season. It is estimated that about 200 dogs were killed by wolves in 1975 in the north-west of the Peninsula. Once again, human thoughtlessness in trying to eradicate natural predators has led to the proliferation of these substitutes for the natural balance.

Wolves of the North

Wolf ( Canis lupus )

Wolf painting

| BUY A CANVAS PRINT:

You can choose a personal size |

With regard to the behaviour within the hunting groups, it can be assumed that there are no hierarchical differences within them other than those imposed by the normal composition of the herds, bearing in mind that those adult individuals participating as "aggregates" in the expeditions do not enter into antagonism with the other dominant adults of the leading herd. This explains why those packs that regularly consisted of four or five individuals during the spring and summer months often receive a considerable increase in numbers at the arrival of autumn, although this happens less and less frequently, due to the regression of the total wolf population. In this respect, our research allows us to speak of a seasonal situation regarding wolves in the Castilian-Leonese region. The wolf remains in stable conditions in an extension of about seven thousand square kilometres, representing 1.3 % of the peninsular territory. In the rest of Iberia, the extraordinary dispersion of the population - except in very specific points of Sierra Morena, northern Portugal and Galicia - explains the hybridisation with bighorn dogs, solitary hunting activities and the spread of scavenging habits. The excessive density of wolves in a given biotope usually triggers an aggressive reaction on the part of the older wolves that monopolise the females, and in this operation they often drive away the younger individuals and even kill them if this can guarantee the hegemony of the dominant ones. The same is true for both males and females. It has also been observed in certain areas of the northwest of the peninsula that the simultaneous occupation of a biotope by several families of wolves causes terrible confrontations between them. Aggressive reactions of this kind also occur in captivity. According to Gerald Menatory, young wolves have been attacked and killed by adults sharing the same living space in an enclosure. It is generally acceptable that such phenomena occur in connection with the courtship display of the male towards the female, as well as in the relationship of both to their grown up offspring of barely a year old. Because, although the latter do not represent an element of rivalry in the process of encelatation - sexual maturity is not reached by the wolf before it is two years old -, the adult male of the pack wants to cure himself by eliminating, if possible, future enemies in this area. The same can be said of females, who may even hurt younger females who might compete with them by attracting males. In any case, this aspect of wolf behaviour is subject to several conditioning factors and we can assure, through the experiences accumulated in research on Iberian wolves in the wild, that although during the rutting season the adult wolves, leaders of the social group, are very irritable and aggressive towards their conspecifics of the same sex, tolerance is frankly good among the different components of the family and it is common to find groups composed of individuals born from a first litter, their parents and with them the offspring born from a later litter. Theoretically, herds of more than a dozen individuals could be formed, but in reality this is not the case. We must bear in mind that a female of three or four years of age is not very prolific in her first births, so that in those cases where there is a union between a pair which is already able to reproduce but young, the total number of individuals in the family will probably reach five or six. In the best of cases, in successive years the same female may give birth to as many as seven or eight cubs. In any case, by the time the cubs reach five or six months of age, their siblings from the previous litter are of mating age and the pack is then reduced, with the desertion of the sub-adults, to the most typical family group at that time consisting of the adult parent pair and the young born in the last spring.

Wolves at dawn

Northern Wolves (Canis lupus)

Wolf paintings

| BUY A CANVAS PRINT:

You can choose a personal size |

Zeal

In winter, usually between the end of January and mid-March, wolves proclaim their love affairs. Males and females pair up and mark out a territory by depositing scat in visible spots, making it easy for other conspecifics to recognise the signs. By this time, the pair has driven other possible members of the group into the chosen territory. Occasionally there are fierce, but rarely fatal, battles between males in a herd for the position of sexual hegemony. In some cases - especially if the population is widely dispersed - the pair may remain together beyond the reproductive period. In other cases, on the other hand, group coherence is maintained during the rutting season in regions with high population densities due to abundant food.

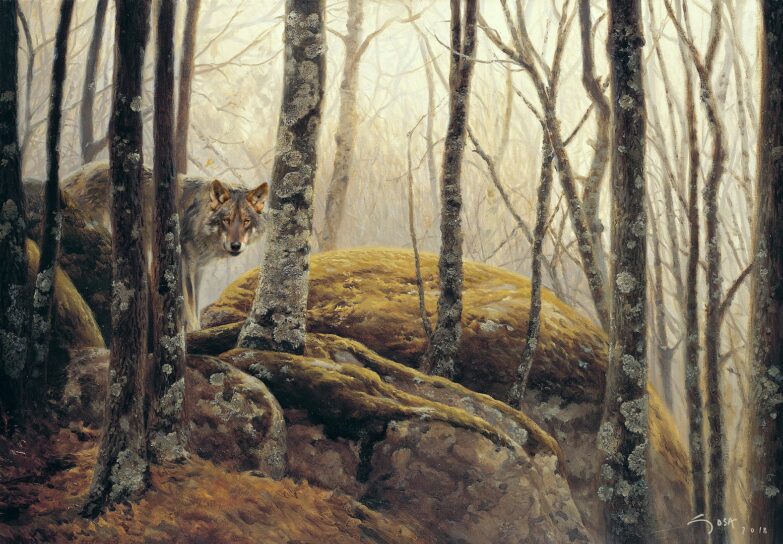

To come across an Iberian wolf in the middle of a forest is almost a dream, as is this painting. For five years I have visited this oak grove next to my house almost every day and I have never seen a single man there. So why are there no wolves? "We shot the last one twenty years ago" Vitorio answers me...' This painting is an oil painting on canvas. Oil on canvas. Manuel Sosa © 1998

The Encounter

Iberian wolf ( Canis lupus signatus )

Wolf paintings

| BUY A CANVAS PRINT:

You can choose a personal size |

The litter

The births take place after sixty days of pregnancy, so that the bitches would generally be born at the end of April or beginning of May, as has been proven in the central-west and north-west quadrant of the Peninsula. Under normal conditions, the she-wolf will give birth to five to seven cubs. For this purpose, she retreats to a solitary and hidden place where she digs a small den or den, although sometimes she uses a simple depression in the ground or a rocky shelter; unusual cases include a litter born in a tunnel, a few metres from the mouth, and dens in open fields of cereal. At birth, the cubs have soft, uniformly dark fur and are fed on their mother's milk for the first three weeks. The appearance of the first teeth of the milk dentition around the fourth week allows the cubs to take advantage of the semi-digested food regurgitated for them by the male wolf, which is also consumed by the female. In this respect, research carried out in the Iberian Peninsula indicates that the mate of the parturient female usually hunts alone, but if the density of wolves and prey is sufficiently high, each male may participate jointly with others in the hunt. This is less and less frequent, due to the precarious situation of wolves in the peninsula. As the cubs become more mature, play takes centre stage in family life, as befits animals with a high IQ. Naturally, it is the youngsters who take the lead in playful displays, and it is common to see them jumping on their parents while nibbling their parents' ears and pulling their tails with the consent of the adult couple, who nevertheless decide from time to time to give their playful offspring a nuzzle. If the mother senses that the location of the litter may have been discovered by a potential enemy - usually man - she will try to settle her young elsewhere by grabbing them by the nape of the neck and carrying them between her teeth. The discovery of wild boar tracks in the vicinity of certain destroyed wolf dens in the Portuguese Beira Alta is indicative, according to research carried out in Portugal by Paico de Magalhâes, of a considerable incidence of these wild noises on the wolf packs. At three months of age, wolf cubs regularly accompany their parents on hunting trips. By this time their fur has already undergone a profound change and soon shows the new greyish-dark shade which is a sign of physiological maturity. It will take a couple of months more for the animal to acquire the true appearance of a cub with full teeth. During this time, learning hunting techniques is a fundamental factor in the normal development of the young wolf's psyche, as are play activities. In this respect, human persecution can cause profound disturbances in the functioning of the mechanisms of the species. As far as the Iberian Peninsula is concerned, the proliferation of hunting at any time of the year, as well as the anachronistic and execrable use of poison, have reduced the wolf population to very dangerous limits. And if, for this reason, the parents disappear and the coordination of the family group breaks down, the balance will be even more dramatic, since, even if some surviving youngsters are lucky enough to be adopted by other adults, the rest will see their integral development interrupted. Returning to the pups' apprenticeship, it should be noted that, as a preliminary phase of their true prefations, the pups embark on a series of what might be called "hunting trials": as soon as the male parent - who, as we have said, hunts for the group - brings a live prey, the cubs play with it, subjecting it to continuous skirmishes in which they display unusual energy, alternating with turns and attempts to escape, which seem to reveal an attitude of strangeness mixed with the curiosity that characterises wolves, as a further symptom of their intelligence. Although there is a popular belief that a wolf can consume almost a whole sheep in one sitting, the truth is that its stomach capacity does not allow it to ingest more than 4 or 5 kg on average, although a wolf can vomit a first part of the meat it is eating and then insist on the dead prey until it devours a considerable amount of it. Anyone who has observed a wolf devouring its prey will agree with us that the meat is eaten in large mouthfuls, which causes the animal to vomit initially, before continuing its feast. This does not occur in well-fed wolves, i.e. those that live in confinement and are regularly fed. The threatening growls exhibited by wolves as they divide up their prey, which they often do in the same place a few metres from their capture, are among the expressions of each individual's di- suasion towards the leftovers. According to observations by R. Grande, in the north-west of the Iberian peninsular, groups of five, seven or more wolves - frequent in certain areas during the autumn and winter months - move either in single file or in double file, but in the latter case it could be proved that they were young individuals. On one occasion - Sierra de la Culebra, Zamora - three wolf cubs accompanying a female and three adult males would occasionally move ahead of the formation, no doubt in a playful mood, which provoked the adults to nuzzle and shove the restless cubs. When running after their presumed prey, the wolves make enveloping movements like consummate strategists. It has been observed that wolves, in groups of three, four and more, made tremendous circles in the snow in remote places, in order to cut off the pursued animal, although their attacks were not always successful. The remains of prey not consumed on the spot are carefully hidden in the undergrowth, in a hole, or covered with earth and dug up again when the animal is hungry again. A wolf will stay in a given territory for as long as the density of prey in the vicinity allows, but does not hesitate to make long journeys in search of food. This predator can cover as much as twenty-five, forty or even more kilometres in a single night, as several authors, including Dr. Boitani, have shown in his studies on Italian wolves equipped with transmitters in the Abruzzo National Park. A quick visual examination of the tracks of an ungulate in the snow gives us an idea of the difference in pressure exerted by them and those left by a wolf moving in the same environment. Thus, while the ungulate sinks into the snow, the wolf manages to move more quickly, because the pressure it exerts on the snowy ground is lower. Therefore, the wolf does not find too many difficulties to move on snow-covered ground, which is important when considering the higher efficiency of this predator in hunting animals in tundras and taigas, as well as in any other biotope where snow falls during the cold season, as it happens in some areas of the Iberian Peninsula.

Iberian Wolf

Iberian wolf ( Canis lupus signatus )

| BUY A CANVAS PRINT:You can choose a personal size varying the original width (cms) |

There are many paintings depicting the wolf in art. There have been cases - verified several times - of wolves chasing prey in the snow, while the flocks of sheep or goats remained uninvoked. It would seem that the carnivore was triggering the behaviour of appetence which, as we know from the relevant ethological studies, drives the animal to perform a series of acts whose object is the desire to hunt rather than to eat. In any case, the wolf is adapted to long chases in which endurance is a quality that compensates for the relatively slower running speed. Cooperation in hunting actions is another constant within wolf groups that still retain their traditional status; but this is unfortunately not the case in all regions where the wolf is part of the fauna, as the dismemberment of the packs prevents the different individuals from being able to carry out all the activities that enable them to engage in profitable community action. It is not surprising that an animal like the wolf, the protagonist of so many gruesome stories, the focus of human hatred and whose life and habits have always remained a mystery, is today on the verge of extinction. Perhaps like no other predator, it has endured the persecution of mankind, not only because of the damage it inflicted on livestock, but also because of the fear it inspired and the mythical character it was given. It is therefore easy to understand why today the wolf is confined to small areas in certain countries. In many places the wolf has disappeared in a short period of time. In fact, it can be said that wolf populations began to decline drastically in the second half of the 20th century. Before that, the species was already extinct in France - until 1930 - and only very occasionally isolated specimens were seen in the south of the country. In England they had been quicker to exterminate them and there were no wolves left at the beginning of the 16th century, while in Scotland they had been wiped out by 1711 and in Ireland by 1770. In Switzerland they fared no better, but were still present in Graubünden and the Central Alps until 1947, when the last wolf was killed. In Germany, too, there was a small population of wolves in the Silegiam in the north-east of the country in the middle of this century, but they are now extinct. In northern Europe, some wolves remain in northern Sweden and Finland - Lapland region - and in Norway. In Sweden they are protected, with the government compensating affected farmers. However, the methods of wolf conservation in captivity, which are to be implemented jointly by various organisations in these countries, are totally inadequate. Although the aim is to commend the wolf by trying to preserve wildlife, such methods, if put into practice, would lead to the forced and unnatural adaptation of the species to be protected to an artificial situation, which would eventually lead to a process of gradual degeneration of the status of the wolf population in question. As a further consequence, their behaviour would be altered and the result would ultimately be disapproving and counterproductive. As far as the USSR is concerned, the different wolf populations remain stable for the time being, and even in some regions of European Russia they enjoy an optimal situation, despite the persecution of wolf control campaigns. In the middle of the 20th century, wolf control campaigns reached highs of between 20,000 and 35,000 animals killed. These figures have not been matched in recent years, and while the results of the previous culls are being called into question, ecologists are discovering the importance of the wolf in the ecological chain. Unfortunately, in the northern regions of Europe, as in the other tundra areas, a new danger has been added to the one posed by human persecution. This is the contamination by radioactive particles from reindeer meat which the wolf eats and which the herbivore has accumulated in its tissues after eating lichen infested by radioactivity from man's nuclear tests. In Central Europe, the wolf remains almost exclusively confined to the Balkan region, which runs for 600 km along the borders of Albania, Yugoslavia, Bulgaria, Greece and Turkey. The wolf is also found in the Carpathian Mountains, particularly in the border area of Poland and Czechoslovakia, as well as in Romanian Transylvania. Only three countries in Western Europe still have wolves. Apart from Italy, Spain and Portugal have a small population with little prospect for the future. Recently, however, a team led by R. Grande carried out an extensive work programme aimed at a more precise knowledge of the status of the wolf in the Iberian Peninsula. In the province of Zamora and in close collaboration with the ICONA of that province, detailed investigations have been initiated in the above mentioned sense, after thorough field studies undertaken three years before. It should be borne in mind that the Canas lupus signatura species finds its best genetic and ecological conditions in the provinces of León and Zamora. In the rest of Iberia, with the exception of areas bordering Galicia and Portugal, the wolf population is extraordinarily dispersed and in some cases their former biotopes have been interfered with or colonised by the marauding dogs. In addition to the above-mentioned creas, wolves remain in the Portuguese Beira Alta, in very specific points in the districts of Evora and Beja on the border with Spain, in the mountain ranges of Caceres and Badajoz, isolated individuals in the Montes de Toledo, in the southern mountain ranges of Salamanca - Peña de Francia and Gata -, a few pairs in the south of Asturias, north of Palencia and Burgos and a few isolated individuals in Tierra de Cameros in the province of La Rioja. In the south of the Iberian Peninsula, the species is also unevenly distributed. The sierras of Madrona, Alcudia and Almadén in the southwest corner of Ciudad Real, plus other small enclaves in Sierra Morena, are home to a small population of wolves totally isolated from the rest of the Peninsula, as are most of the wolves. We think, like Jesús Garzón, that the Iberian subspecies Canis lupus sígnatus is in danger of extinction in the short term if the dramatic regression it has been suffering in the last ten years continues at the same rate. Moreover, the future of the wolf in the Iberian Peninsula runs parallel to the future of the hunting reserve of Sierra de la Culebra (Zamora) and also of a possible integral refuge. In the same way, although perhaps with greater difficulties, wolf conservation reserves could be set up in the south for the conservation of the wolf in its wild state. The confinement of wolves in reserves would not be advisable as it would make the necessary genetic exchange difficult, would create unnatural conditions, would increase the risk of epizootic diseases and, more importantly, at such extremes, would itself eloquently denounce the disruption of natural habitats and the unbalancing of ecological harmony even more than it is today. Indeed, if in so many other countries the great mistake has been made of exterminating any species or reducing its chances of survival before getting to know its ecology, this should help us to try to avert a similar danger in the case of Spain and Portugal. The disappearance of the Iberian wolf would imply the evidence of a general inoperativeness in what is everyone's duty: the protection of each and every species. For the time being, the inclusion of the wolf as a game in the hunting catalogue of Spain and Portugal would theoretically protect the predator. Although the respective governmental bodies have pronounced themselves in favour of this, this has not prevented the wolf from continuing to be hunted and hunted in a variety of ways. According to our information and checks, this accounts for one-fifth of the total. Of these, 80 % are killed illegally. Paradoxically, in many cases, it is the administration itself that is involved in the more or less direct eradication of wolf populations, especially in state-supervised hunting grounds. In Portugal, the species is not faring any better, although the programme set up by the team headed by Paico de Magalhâes and aimed at the preservation of the species is already supported by specialists from the World Wildlife Fund and their studies on the ecology of the wolf are producing good results. In the same country, the Peneda-Geres National Park is the only refuge for Canas lupus signatura. For this purpose, about half a million escudos are paid annually in the Peneda-Geres livestock areas as compensation for wolf attacks on herds. It was also a question of introducing some amendments to the hunting regulations, as far as the wolf is concerned. Indeed, Magalhâes has drawn attention to the extension of the wolf hunting season until the last Sunday in March, thus covering, inappropriately, the rutting season. In Spain, the legal hunting season for wolf hunting with firearms closes on the third Sunday of February. Concerning Italy, Dr. Tazzi and Dr. Boitani lead a team that is developing important work on the status of the wolf in the central and southern Apennine region. In particular, Dr. Boitani has already carried out a first phase of study in the Abruzzo National Park, located within the core areas of the orographic chain in question. Sponsored by the World Wildlife Fund, Dr. Boitani has carried out detailed research since 1973. Subsequently, a second campaign was carried out in which the data obtained earlier was augmented by an ecological survey on the dynamics of the wolf population. In the end, it is to be hoped that the national conscience of each country will realise in time that it has made a mistake in its relations with other living beings, but if awareness is slow to penetrate and in the meantime species become extinct, the imposition of energetic measures should be a first step in the programmes for their preservation. In the case of the wolf, we are working to ensure that the species survives without seriously interfering with the interests of livestock farmers, but the responsibility to protect a species, whatever it may be, by preventing its extinction, is everyone's business. Anyone who claims the right to eradicate a species from its natural habitat, bringing it to the brink of extermination, deserves to be repulsed by any clear and sensible mind, for in so doing he is clearly demonstrating that he is using his ignorance or bad faith to pedantically contest what millions of years of evolution have worked out to achieve perfect harmony in the biosphere. It is essential that we learn to know and respect the role of each and every species that still co-exists with man on planet Earth, before the unfocused work of man completes its uninterrupted destruction.

The authors

Article from the encyclopaedia of Iberian fauna by Felix Rodriguez de la Fuente, illustrated with the paintings of Iberian wolves by the painter. Manuel Sosa. You are invited to enjoy his complete work on the website of his gallery.